'It's a complete admission that you're not managing anything': academic on why fauxductivity is management problem

Another study is out about latest employment trend “fauxductivity”, taking a closer look at why employees are pretending to busy at increasing rates.

It’s not simply laziness or dishonesty — it’s a deliberate way to get attention they’re not getting enough of – and it’s up to managers to fix it, says one academic.

“It's not employees, it's managers. It's managers who are using unfair metrics that people are gaming, because they don't feel it's unfair to game an unfair system,” says Jean-Nicolas Reyt, associate professor of organizational behaviour at McGill University in Montreal.

“They want to look valuable to the organization, they want to have a promotion, they want to have a salary increase – it's important to them, right? So that's why they do that. The issue is that they're spending a lot of time doing it.”

Performative work – or fauxductivity, as it’s being called recently – occurs when employees focus on tasks that create the appearance of being busy or productive, rather than on work that drives meaningful business results.

The survey, conducted by people analytics firm Visier, shows that performative work is usually motivated by a desire to appear valuable – to managers, peers, or company leadership. While occasional instances of such behaviour may be harmless, the Visier survey found that for many employees, productivity theatre has become a significant part of their workweek.

Source: New Survey: Performative Work and Productivity Theater | Visier

The problem is one of performance metrics, says Reyt, explaining that measuring performance according to hours worked and when they worked, or keystrokes or time spent on a screen, means employees will eventually stop focusing on outcomes and begin “gaming the system”.

“The only reason we have the same hours for everybody is because at one point in our history, everybody was a factory worker, or most people were factory workers,” he says.

“This has changed. You don't need to work at the same time and in the same location as everybody else in your organization, because you're not tied to them, that's not how it is.”

The survey, which interviewed 1,000 full-time U.S.-based employees in February 2023, found that 83% of respondents admitted to engaging in at least one form of performative work in the past 12 months. For some (43%), the time spent on these tasks adds up to more than 10 hours per week.

Performative behaviours are varied but share one common thread—they focus on visibility over value, the report says. The most frequently cited behaviors include:

Reyt reiterates that all of these actions are a signal that performance is being measured by the wrong parameters which is, at its core, a management issue.

“If you're in that situation where you're actually caring about how long people spend at their desk, and if they're typing, and do they look busy, you need to reassess your management skills,” he says. “To me, it's insanity. It's a complete admission that you're not managing anything. It's an admission that you do not know what's going on.”

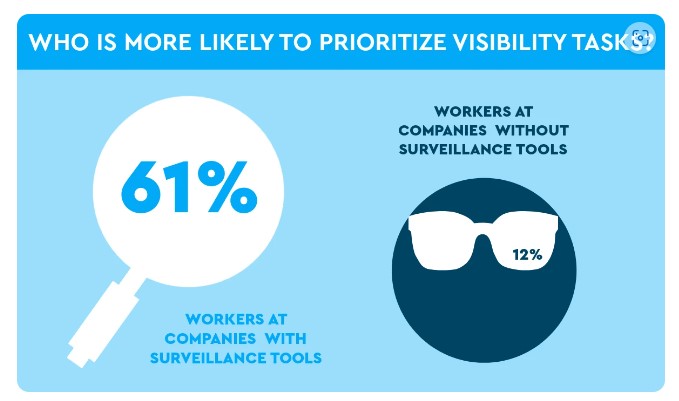

The survey reveals a significant link between employee surveillance tools and performative work or fauxductivity.

According to the report, employees whose companies use surveillance technologies are more than twice as likely (61%) to engage in exaggerated performative behaviors such as keeping a screen awake while not working, asking colleagues to handle tasks on their behalf, or embellishing status updates.

Source: New Survey: Performative Work and Productivity Theater | Visier

“It's a little bit of a chicken-or-the-egg situation. In my opinion, if you feel that it would be tempting to you to install a spying software on your employees’ PCs, then the question is, why are they your employees? Why is everybody in your company dishonest, that you have to do that?” Reyt says.

“This is not how you measure productivity. This is not by looking if somebody is moving a mouse. And especially because, in a lot of jobs today, people have to do very complex tasks, and when they have to do very complex tasks, it doesn't really matter how long they spend doing it — what matters is that they're doing it right.”

While it may be tempting to focus on visible indicators of productivity, says Reyt, he urges HR professionals and employers to instead take a deeper look at how work is being prioritized in their organizations.

By reducing the pressure to look busy and encouraging more meaningful work, employers can boost both employee morale and business outcomes. But the focus has to be on fairness in how performance is measured, and also communicating that to employees, he adds.

“It’s as important to have a fair system as [it is] to communicate about the fairness of the system and make sure that everybody understands what the rules are, what the metrics are, what the steps are, what the review is,” says Reyt.

“Everybody needs to be very clear. You never deviate. And if somebody tells you that your system is unfair, you challenge them and you fight them because it's not unfair, because you know that if they believe that it's unfair, then you can't say ‘no’ to them, because then they start sabotaging their work, they start reducing their input, they start talking into your back…they quit.”

Reyt recommends giving employees attainable yet challenging goals, and measuring output and quality of work instead of things like attendance or arbitrary quotas. It should be a collaborative process with involvement from management and employees, he says – and the acceptance that performance measures evolve.

“If you have somebody who's doing a job, look at whatever output they have, [create] a metric for the quality of that of that output, and then you give them all the resources, and you explain to them that it's a fair thing, and you convince them if they challenge you, and if they make a good point, then you improve the metrics.

“It's about telling people: ‘Let's work together and try to understand what your output should be, and then we'll do that.’”