Stats show New Zealand businesses are some of the least likely to accept and trust artificial intelligence

New Zealand has one of the lowest usage rates of artificial intelligence, according to a comprehensive new global study on trust in AI, with less than a quarter of employers saying they have suitable training in place.

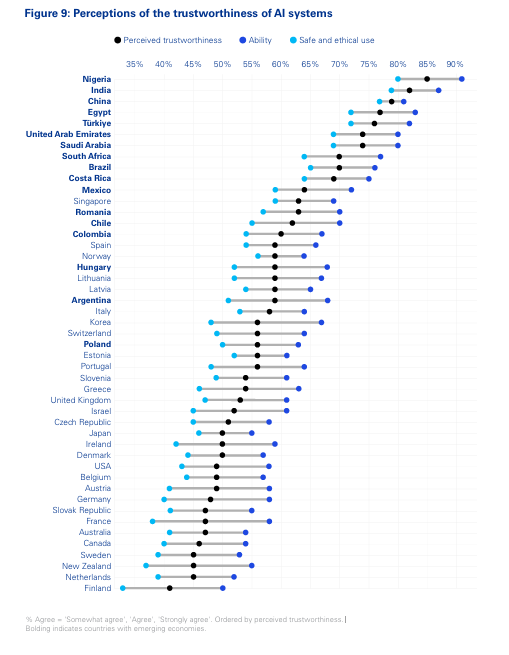

The Trust in Artificial Intelligence Global Insights, released by KPMG, found about 37% of respondents in New Zealand believe that AI is used safely and ethically.

The report warned many organisations are rolling out AI without ensuring proper oversight or AI literacy, creating a "complex risk environment" and that Australians want to see better regulation and governance.

The study surveyed more than 48,000 people across 47 countries between November 2024 and January 2025 and found trust remains an issue - with 54% globally "wary" of trusting AI.

“Of the advanced economies, trust is highest in Norway, Spain, Israel, and Singapore (all more than 50% willing to trust). In contrast, Finland and Japan rate the lowest on trust (25-28%) while New Zealand and Australia (15-17% high acceptance) rank lowest on acceptance,” the findings state.

This is a sentiment echoed in research from ELMO Software, who say 93% of New Zealand HR professionals believe AI will significantly impact their department in 2025, as part of their 2025 HR Industry Benchmark Report.

HRD spoke to Megan Blakely PhD, Lecturer in Teaching and Admin at the University of Canterbury, who says the country’s uptake in AI isn’t a bad thing – and could give a competitive advantage down the line.

“New Zealand’s culture is based on face-to-face contact. People not trusting robots and machines is nothing new. The flip side of delay is wisdom. Just because we’re not jumping on board straight away doesn’t mean we’re missing out. There’s plenty of examples of mis-calibrated trust, which is dangerous.”

Blakely also noted that now, we are seeing more ‘under-trust’, which was noted as positive to businesses who can better educate, implement and train staff effectively.

“We have an opportunity to correctly implement governance around this by taking our time and figuring out what works and what doesn’t,” Blakeley told HRD.

“Ensuring we get the right balance of trust doesn’t happen overnight, so by taking our foot off the accelerator we are able to better gauge things like impact and inconsistencies which will benefit us more in the long run.”

Strategically, Blakeley noted that slowly managing change could be best for business – as you can “iron out any issues.”

“I’ve worked with businesses, and I find that sometimes just because someone in management thinks something is a good idea, doesn’t mean everyone agrees – the false consensus effect. AI is the ‘in thing’ at the moment and people are starting to wise up to it’s uses, but if you roll something out in a slow and controlled way, you’re finding a middle ground between adoption and falling behind. You can build trust instead of destroy it”

“I see big problems brewing for the future – people will start using AI for things they shouldn’t because they don’t understand the impact on people. We don’t have the education or the infrastructure to deal with major catastrophes, so we have to be considerate,” Blakely emphasised.

Unlike other countries globally, Blakely noted the importance of remaining culturally sensitive to New Zealand’s Māori population when managing change – emphasizing the importance of traditional teachings.

Principles of leadership within Māori culture, or Rangatiratanga, embody autonomy and self-determination. Many principles need to be respected when governing and educating people on emerging technologies.

“We need to consult with our Maori and Pasifika people as we implement AI to ensure buy-in,” Blakely emphasised. “We need to put huge amounts of consideration into that. Culturally, we need to consider if this use of technology is appropriate.”

“For example, in Māori culture, separating life from death is important – so there may be taboo in storing data that could be culturally sensitive of those that are no longer with us, for example in facial recognition technologies. We need to replicate other countries systems and processes and work with different cultures and diversity of thought on technological issues,” she added.